Originally published in the Jewish Educator, Winter 2024/5784 edition.

“Before Dr. Fripp’s visit, the Holocaust felt like a terrible historical event that we were researching in class. I didn’t really understand it on a more personal level. After Dr. Fripp’s visit, I had a better understanding of how the people felt.”

This quote comes from one of forty students in a 9th grade Humanities class I had visited the previous week. I introduced them to three people: Holocaust survivor Margot Jeremias, Holocaust survivor Dr. Vera Goodkin, and Holocaust victim Yitzhok Rudashevsky. All of these people were teens, about the age of the students, at the time of the Holocaust. None of them were actually in the room, of course. Instead, I was telling their stories.

Storytelling of this nature can be a powerful addition to a classroom curriculum. “The value of storytelling was incalculable,” the Humanities teachers told me. There are many different ways to incorporate storytelling into a classroom. Each has its advantages.

Single class with multiple stories

When I came to the Humanities class, I brought three stories to them in one 90-minute class period. The stories were chosen to fit with the Holocaust unit they were currently working on in class. Each story was 10 to 15 minutes long and was preceded by some background and followed by a question-and-answer period. As part of the Q&A, we discussed how the story connected to the learning objectives of their current unit.

In this particular case, one of the stories, Margot Jeremias’, was told not by me but by my daughter Esther. Esther was one of the students in this particular 9th grade class. A teen teller like Esther is a special treat for students in a number of ways. She is a peer, one of their classmates, someone they know well. She is also telling the story of someone who is close to her own age. When we hear Margot tell Margot’s story in her video testimony, we are hearing the story of a 12-year-old told by an old woman. When we hear Esther tell Margot’s story, we are hearing the story of a 12-year-old told by a 15-year-old. It sounds very different.

One of the advantages of this method is that it only takes one class period. A single class can be easier to set aside than several classes. In this class, students have the opportunity to interact with the storyteller(s) directly, giving them an important method of engaging and coping with the stories.

Stories told in class are best told in a small group, 20 to 40 students at most. Having too many students in the room prevents individual students from interacting with the storyteller(s). In a large auditorium, students will be less engaged than in a classroom. If you have many classes, it is advisable to tell the stories to each class separately.

Story-infused lesson

A related option is to use shorter stories and interweave them with an historical lesson. In this case, the stories could be five to seven minutes long and built into the lesson. This can be done with one person teaching and telling but is often better with two voices, an educator and a storyteller.

The advantage of this method is that it provides a stronger historical focus to the stories. Stories can be chosen and placed in the lesson with a particular goal in mind. Students again have the chance to interact with the storyteller directly.

Stories throughout the semester

If time permits, bringing storytellers to class on multiple occasions can add significant depth to a unit. In this scenario, some classes are dedicated to learning the history of the Holocaust and others are dedicated to storytellers. Each “story” class has a single storyteller, potentially allowing for longer stories. Storytellers can be chosen to fit the section of the unit being covered at, or just prior to, the time that they come in.

With a single storyteller, students listen, appreciate, and ask questions of the storyteller. Teachers have the option to allow students to try Holocaust storytelling by retelling pieces of this story in partners. Students who have done this have told us that working with a story in this way deepened their understanding of the story they heard.

Students as Holocaust storytellers: Single or multi day storytelling workshops

The idea of having students tell Holocaust stories can go beyond retelling a story they heard. Full class workshops can give students a chance to interact with primary sources and try out the process of developing a story. Multiclass workshops can give students the opportunity to actually develop a story based on a primary source.

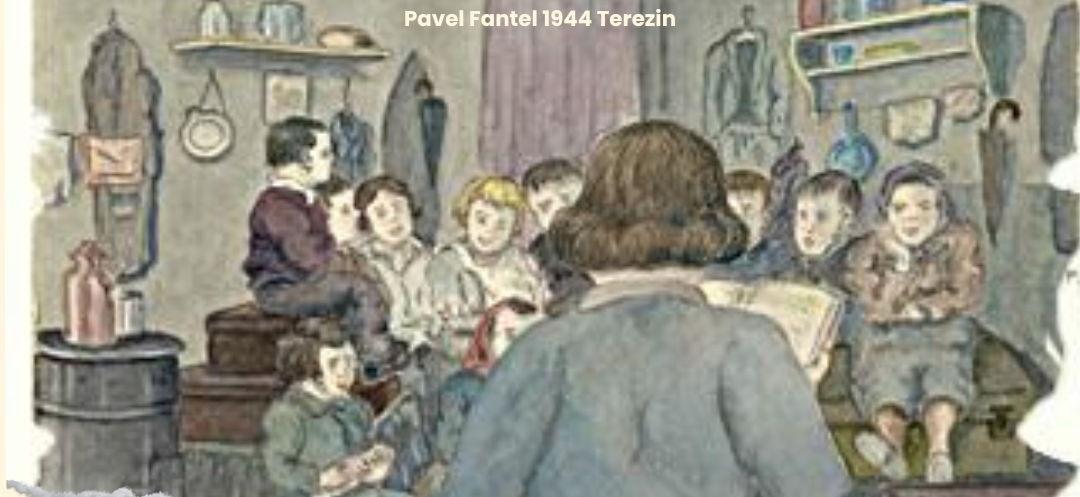

Workshops begin with a demonstration of the process of moving from testimony to story by first describing an image from the testimony and then developing that image into a scene. In a single day workshop, students have the opportunity to take a testimony to a partial scene. In a multiday workshop, students create multiple scenes from a testimony or other primary source. These scenes go together to form a story.

Students work in partners or small groups through this step-by-step story development process. Story development occurs through appreciation – positive feedback – rather than suggestion and critique. This allows the student freedom to build a story themself. We have had remarkable success building stories primarily through appreciation rather than critique.

It is important to note that the stories students are telling should be true stories. Learning to be a “Holocaust storyteller” does not mean learning to make up stories about the Holocaust. Learning to be a Holocaust storyteller means learning to take a primary source like testimony, memoir, or diary, and retell the story told in that testimony in a compelling way. The best storytellers tell the story of someone’s Holocaust experience from inside the story itself, rather than from a distance, shifting from the “10,000-foot” view to a 2-foot view.

For a single class workshop, students are given small sections of primary source testimony to work with. Teen diaries can be a good source. Testimonies should be chosen to be understandable to the students based on their current knowledge of the Holocaust.

For multiclass workshops, students will need to pick a story that speaks to them. Some students might want to share a family member’s story. Others may choose a book that was meaningful to them. Some will need help choosing a primary source. No matter whose story the student learns to tell, they will create a deep connection to that individual. This Holocaust story becomes part of their own story. By helping students learn to tell these stories, we also help the students learn to tell their own stories.

Teachers as Holocaust storytellers

Although it can be advantageous to bring in an outside storyteller, there are many advantages of classroom teachers being storytellers themselves. When educators receive training in storytelling and in developing new stories, they can bring stories into every part of their curriculum. Stories can be included in every lesson, with the story’s length geared to fit the needs of that lesson. When the educator is a storyteller, every lesson can be a story-infused lesson.

0 Comments